The central thesis of Jacques Rancière’s philosophy of art is that art introduces changes in the partition of the sensible. This doesn’t mean that art’s primary function is to think, say, express or do something (although it does that too). Rather, it means that art transforms and renews the (existing) ways it is possible to perceive, think, say, express or do something in the first place. And while doing this, art also transforms subjectivity – it creates new subjectivities.

In a specific way, this is also the effect exerted by Paul Kuimet’s recent oeuvre – an oeuvre that is quite easy to describe but quite difficult to address meaningfully. (This difficulty can initially be characterised through the following question: how to meaningfully address something whose impact wholly precedes meaning?)

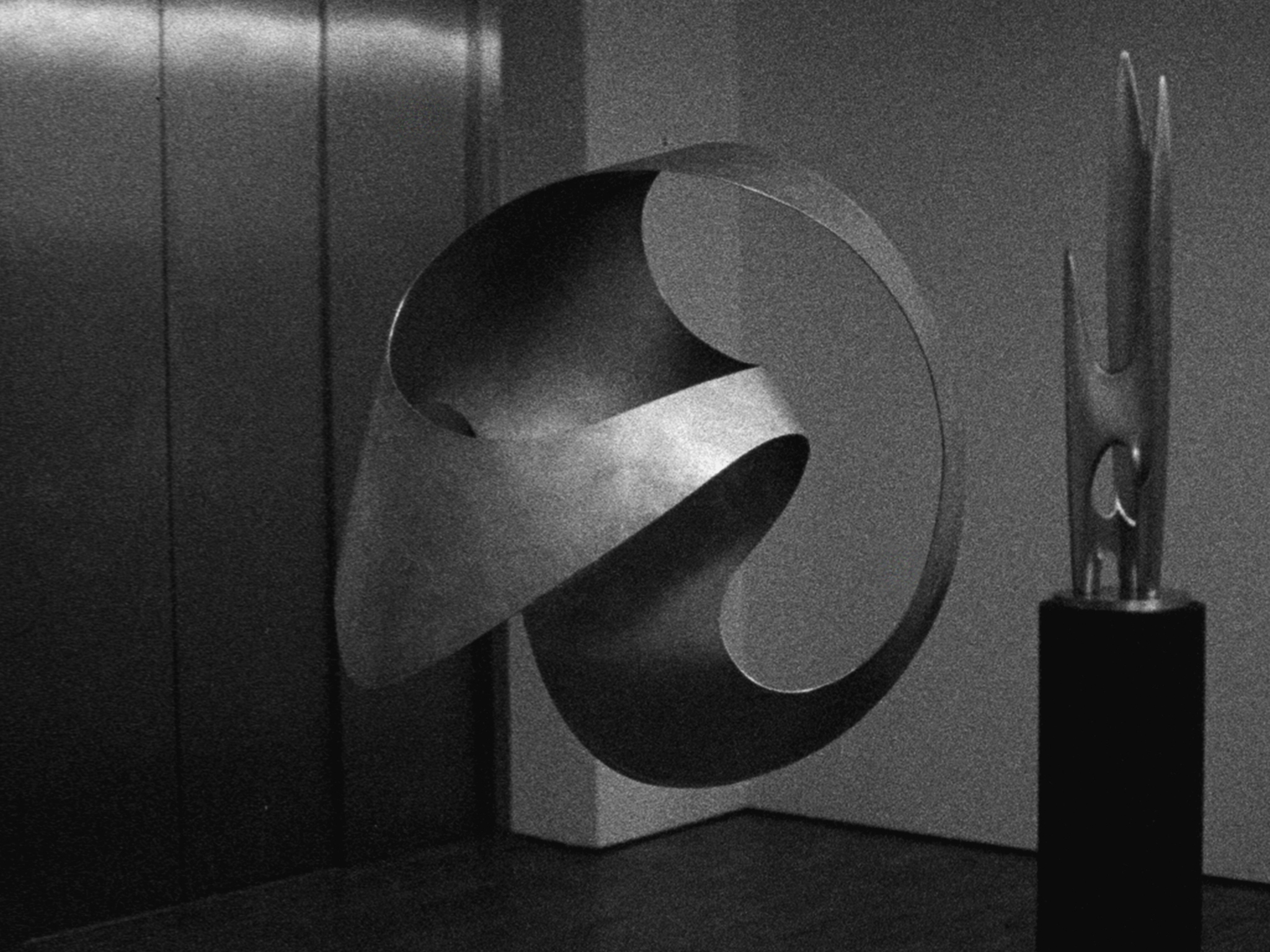

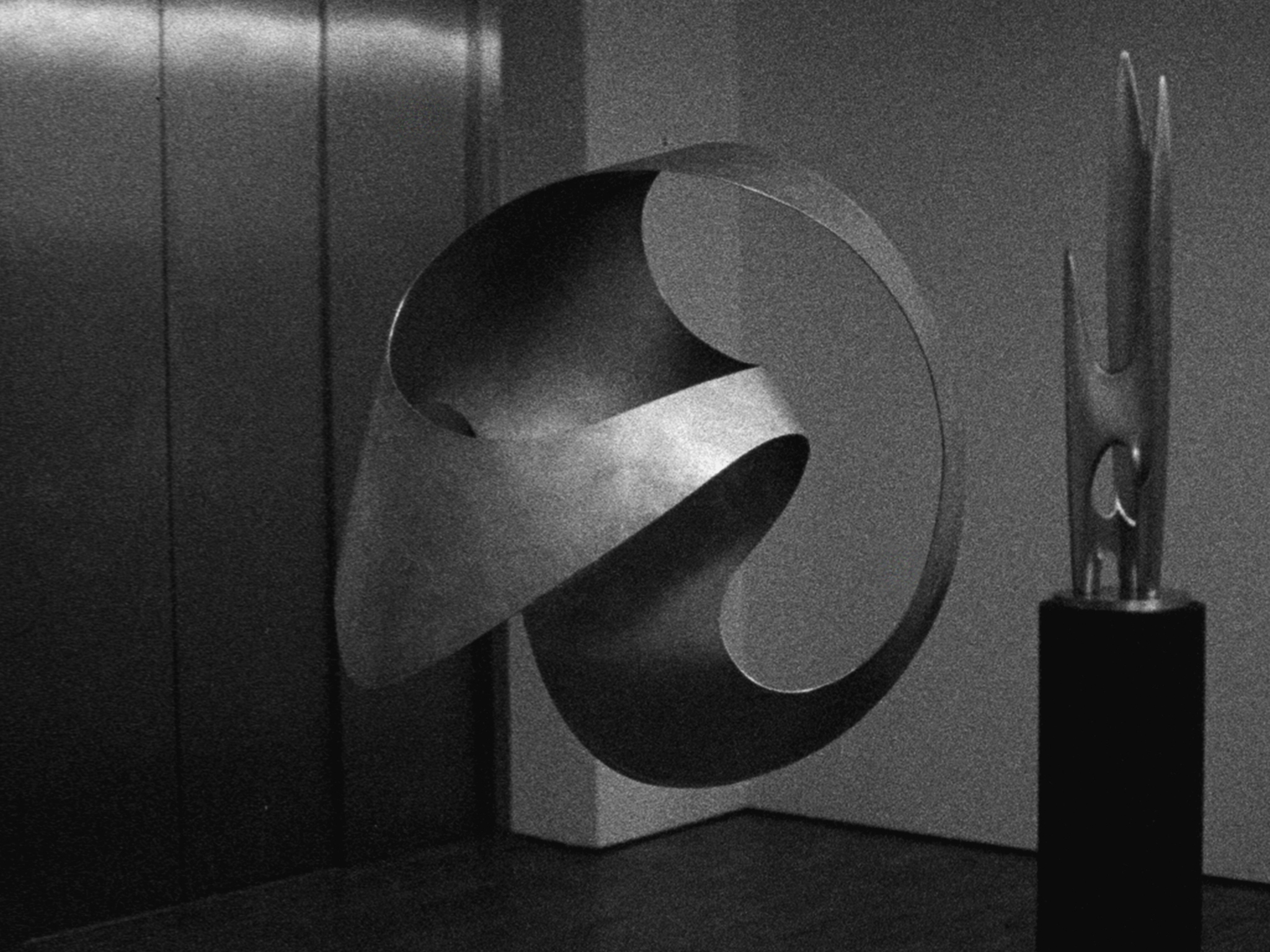

In Kuimet’s recent works, one can detect a few clear-cut formal and thematic tendencies. Starting with the 2013 Horizon,

If one is to look for injections of (social) criticism in Kuimet’s works, it is probably best to study precisely the choice of these thematic motifs: on the one hand, the cultural and historical connotations of the buildings depicted in the lightboxes – the Atomium, built for the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair (Perspective Study, 2016);

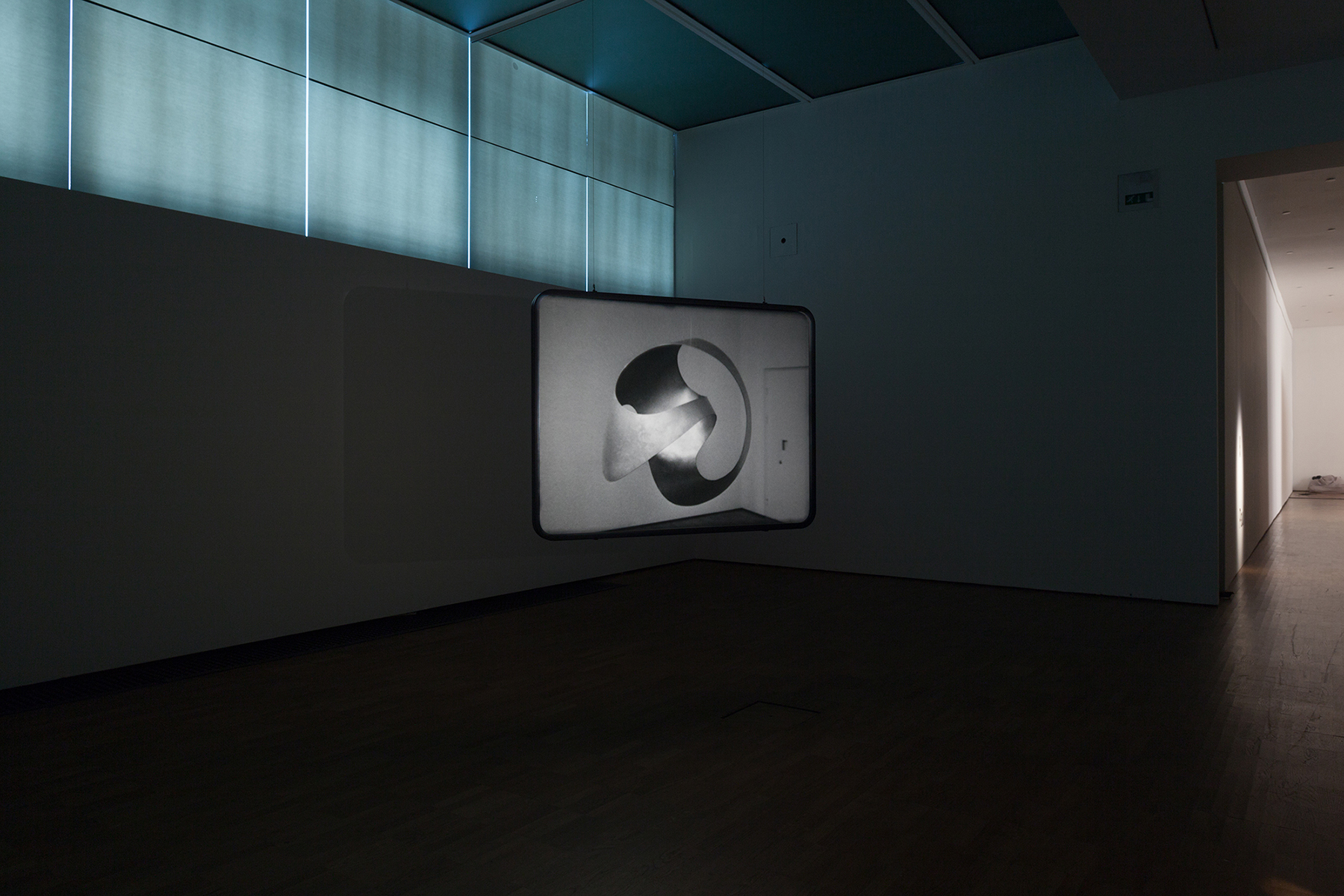

But I will argue here that despite the rather distinct choice of these objects, and the possible joint critical narrative they might make up, these thematic motifs, along with whatever “content” or social meaning they might connote, are altogether secondary in Kuimet’s recent oeuvre – in any case, it is very difficult to recognise them as something “meaningful”, since the buildings in the photographs are fragmented and the sculptures are almost non-figurative and extremely mute. Of much greater significance are the ways in which these objects are presented in the overall construction of space, and the purely perceptual impact they exert on the viewer. We can be quite sure that Kuimet’s installations realise the work of pure form: responding to a specific impulse, they transform the familiar ways in which bodily perception is used to confront the surrounding material reality. If I had to name and specify that impulse, I would call it a certain kind of productive frustration with photography’s traditional (and therefore seemingly inevitable) features: with its two-dimensional and static nature, and with its predominantly singular perspective.

Kuimet’s work tries to overcome these seemingly inevitable features in various ways that all challenge well-known oppositions related to the visual arts in general. The two photos in the lightboxes of Le Lys (2014)

Kuimet’s productive frustration with photography’s traditional absolutes results, on the one hand, in the spatial sculpturalisation of the photographs (the lightboxes) and, on the other hand, in the virtualisation of the sculptures (the screens) – in the dissolution of the viewer into the scene (the films) or in the dispersion of the viewer into the darkness (the lightboxes).

All of these observations are, in essence, insufficient descriptions of completely perceptual affects. Words fundamentally fail to meaningfully address Kuimet’s works for one very specific reason: namely because words, meaning and ultimately “language” itself are completely secondary and utterly late with regard to such kind of art. The transformative impact of these works primarily exerts itself on the level of affect – in the purely bodily and perceptual experience of the recipient. This kind of experience fully takes place long before the “meaningful” intervention of any kind of language – it is first and foremost an experience that precedes all meaning and therefore, in a sense, all subjectivity. Following Fredric Jameson, we may also say that these works primarily realise their transformative and enriching potential on the affective level of bodily consciousness. Jameson differentiates such kind of mere bodily consciousness from subjectivity that is, for him, a purely lingual and meaningful phenomenon and, as such, only an object for this consciousness. Following this division, Jameson also rephrases the notion of “emotion”: he re-names conventional emotion that belongs to the sphere of subjectivity as “named emotion” (delight, sadness, etc.), and differentiates it from affect, which is a purely pre-subjective and bodily phenomenon that is felt on the level of “mere” consciousness and cannot be accessed through language. In Rancière’s terms, it is safe to say that Kuimet’s work precisely redistributes the sensible on this affective level of pure consciousness. It does not convey some clear-cut (cultural, critical or whatever) meaning to us and does not associate with any clear cut “meaningful” emotions; instead, it transforms our bodily potential for perception on a much more immediate and primary level – that of the impersonal present of the body, in regards to which subjective “meaning” is completely secondary. Therefore, I’ll venture by claiming that the impact of these works in not based on whatever “meaning” they might convey, but on their simple spatial and material presence.

Jaak Tomberg (b. 1980) is a literary scholar and critic based in Tartu, Estonia.

His main fields of research are literary theory and science fiction literature.